This text assumes that you have a general idea about the following:

- Regular Expression

- Finite State Machine

Ken Thompson wrote Grep in a single night. Here, you’ll understand how to build a mini grep in a single night, assuming that you can finish this text and implement it in a single night. You’ll learn how with how to do so using Finite State Machines (FSMs). I’ll not be showing the entire source code here. I’ll be referring to snippets of the original source code to show how it makes use of FSM. This text is not a step-by-step tutorial, but is supposed to give you a general idea of building a simple version of Grep using the concept of FSMs.

Starting Easy

Let’s say you’re trying to search for a literal string lucky in a large text file. It’s pretty easy. You’ll do the following (or atleast something similar to this):

- Start scanning the text file

- If the current character is

l:- Start another scan of 4 subsequent characters starting at the current character

- Check that the next 4 characters are

u,c,k,y, in that order. - If yes, jackpot!

- If no, halt the inner scan and return to the outer scan.

- If the current character is not

l, move to the next character.

Although this can be wildly optimized, this logic breaks down if we’re dealing with regular expressions. A simple expression like hel+o will be very difficult to deal with. Furthermore, it’s likely to get complicated real quick if we want the tool to deal with a complex pattern like ^I see \d+ (cat|dog)s?$.

Nondeterministic Finite State Automation

If you’ve taken an undergraduate course on Computational Theory or Discrete Maths, you must be familiar with this topic. They facilitate searching for a text using regular expression (just like what grep does). Let’s recap the topic.

A regular expression is equivalent to a NFA. It means, every regular expression has a equivalent NFA that will approve of the string if that string is also matched by the regular expression.

A NFA has the following:

- A set of states

- A finite set of input symbols (which will be ascii text in case of our version of grep)

- A transition function that defines what the next state should be if a certain input is encountered

- An initial state

- A set of final states

- If we land on any of the final states after we’ve read all the input, the machine is said to have approved the input text.

- If we land on any of the final state before the all of the input text has been processed and there are no transitions from the final state, the input text won’t be approved.

- If we don’t land on any of the final states after all of the input text has been processed, the input text won’t be approved.

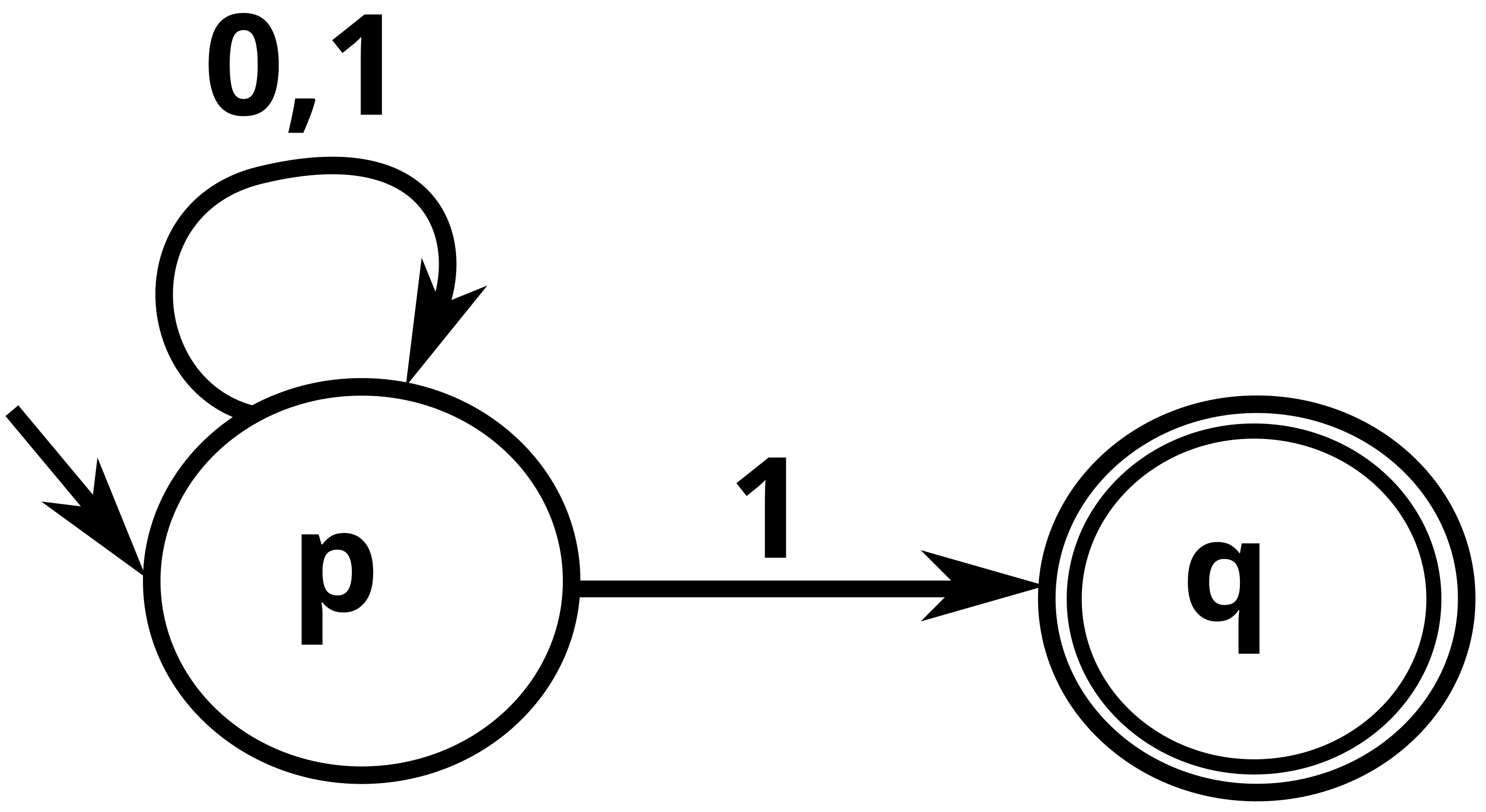

For example, consider the following NFA:

This NFA approves of the string that ends in 1. In other words, it is equivalent to the regular expression (0|1)*1.

This NFA has:

- A set of states:

pandq. - A finite set of input symbols:

0and1- This means our input text will consist only of

0s and1s

- This means our input text will consist only of

- A transition function

- Shown by the diagram

- If we’re on state

p:- If we encounter a

0, we stay atp - If we encounter a

1, we can either stay atp, or transition toq. This is non-deterministic. More on this below.

- If we encounter a

- An initial state:

p- Shown by the arrow on

p.

- Shown by the arrow on

- A set of final states

- State

qis the final state.

- State

Now, let’s unpack that non-deterministic part. If we’re on state p and encounter a 1, we’re ‘free’ to stay at p or transition to q, i.e. instead of a single current state, we have multiple. We may start out on a single initial state. But, if we encounter any non-deterministic transition along the way, we’ll be at two different states simultaneously. From there onwards, we calculate what the next state will be for all the current states we are in using the transition function.

In other words, you can imagine the universe splitting into two (or more) versions of itself once we encounter a non-deterministic transition. Each splitted version may re-split if it encounters another non-deterministic transition.

If the input string ends in 1, for eg 010100111, at least one current state will have remained at p before encountering the last 1 in the input string. This is because every time the non-deterministic transition was encountered in the above figure, one transition always chose to remain at p, making one of the current states p. And at the very last transtition, this current state can choose to make a transition to q and hence land on the final state after all of the input have been processed.

On the other hand, if the string is 010.

After the first transition, the current state will be

p, because there’s no non-deterministic transition for0.After the second transition, we’ll have two current states, one at

pand one atq.After the third transition:

- The current state at

pwill stay atp. - The current state at

qwill be rejected because there are no any transition function for0at the stateq.

- The current state at

Extracting expressions

The program we’re trying to build should extract individual expressions from the regex string. For example, the regex ^I see \d+ (cat|dog)s?$ consists of the sequence the following expressions:

- Literal expression

I - Literal expression

(space) - Literal expression

s - Literal expression

e - Literal expression

e - Literal expression

(space) - One or more quantifier of the expression:

- Digit expression

- Literal expression

(space) - Alternation of the expressions:

- Sequence of literal expressions:

cat

- Sequence of literal expressions:

dog

- Sequence of literal expressions:

- Quantifier (min = 0, max = 1) of the expression:

- Literal

s

- Literal

A regular expression, thus, is always a sequence of individual expressions, which themselves may be nested. This text will not cover parsing either. You can use Pratt Parser, Recursive Descent Parser, or any other parsers for that matter.

Now, assuming that the regular expression has been parsed into a sequence of individual expressions, we move on to the main part of constructing the NFA for the regular expression. We do this piece by piece, starting from the easier ones.

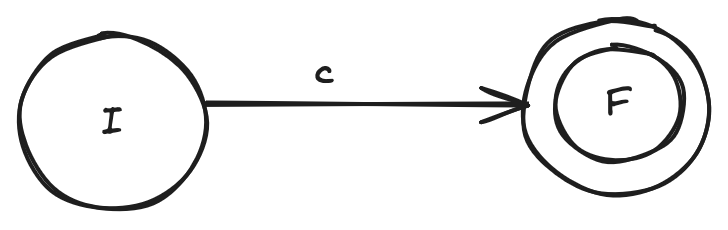

NFA for a single character expression

Let’s deal with the very simple case first, where the regular expression consists only of a single character. For eg, searching for z or l in a text.

This is very easy. We construct the following NFA:

This NFA will allow us to make a transition from the initial state I to the final state F if our desired character, let’s say, c, is encountered. Pretty straight forward!

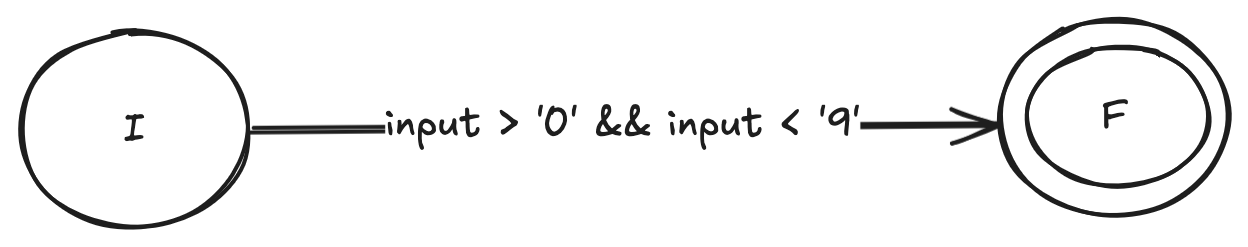

NFA for a digit expression (\d)

Constructing an NFA for a digit character (\d) is similar to constructing one for a single character expression.

The NFA will make a transition to the final state if any character whose ASCII value is greater than '0' (0x30) and smaller than '9' (0x39) is encountered.

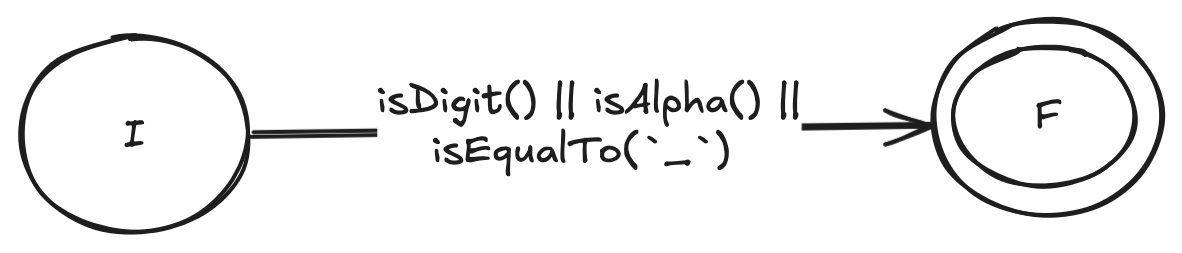

NFA for an alphanumeric expression (\w)

The NFA for an alphanumeric character (\w) is also a piece of cake.

The NFA will make a transition to the final state if the character encountered satisfies any one of the following constraints:

(c < 'a' && c < 'z') || (c < 'A' && c < 'Z')(c > '0' && c < '9')c == '_'

NFA for a wildcard expression (.)

I’m not even going to show you the NFA here. You can figure it out, honestly!

Combining the logic for single character expressions

// getSymbolCompliantFunction will return a function that will return a bool.

// It returns a function that returns true if the character supplied to that function is the desired token.

func getSymbolCompliantFunction(token tokenizer.Token) func(symbol byte) bool {

return func(symbol byte) bool {

switch token.Type {

case tokenizer.Digit:

return symbol >= '0' && symbol <= '9'

case tokenizer.AlphaNumeric:

return (symbol >= 'a' && symbol <= 'z') || (symbol >= 'A' && symbol <= 'Z') || (symbol > '0' && symbol <= '9') || (symbol == '_')

case tokenizer.Literal:

return symbol == token.Character

case tokenizer.WildCardDot:

return true

default:

panic(fmt.Sprintf("Cannot return symbol compliant function. Character: (%s)", token.Character))

}

}

}

// NFA yields a desired NFA for the single chracter expression (digit/alphanumeric/literal/wildcard)

func (a *SingleCharacter) NFA() *nfa.NFA {

nfa := nfa.New()

// Add two states

// Mark the latter one as the final state

startState := nfa.AddState(false)

endState := nfa.AddState(true)

// Mark the former one as the initial state

nfa.Start = startState

// Add a transition function such that the transition occurs only if the desired character is encountered

nfa.AddTransition(startState, endState, getSymbolCompliantFunction(a.Token))

return nfa

}

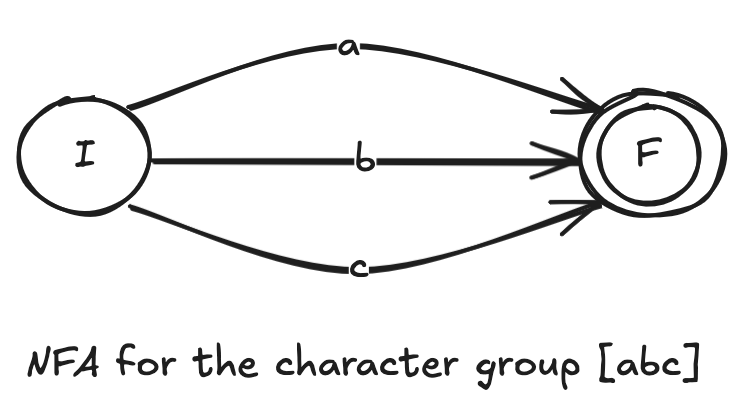

NFA for Positive Character Group

A positive character group matches a character if the character encountered is among any of the characters inside the group. For eg, for the group [abc], the regular expression satisfies either a, or b, or c. Easy as a breeze!

The NFA will make a transition to the final states if any character inside the character group is encountered.

Alternatively, we also could’ve done this using a single transition that returns true if the encountered character is present in the character group.

func (a *PositiveGroup) NFA() *nfa.NFA {

nfa := nfa.New()

startState := nfa.AddState(false)

endState := nfa.AddState(true)

nfa.Start = startState

for _, match := range a.ListOfMatches {

nfa.AddTransition(startState, endState, getSymbolCompliantFunction(match.Token))

}

return nfa

}

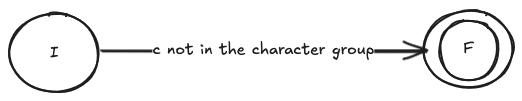

NFA for Negative Character Group

A negative character group matches a character if the character encountered is not among any of the characters inside the group. For eg, for the group [^abc], the regular expression satisfies any character except a, b, and c.

The NFA will make a transition to the final state if the character encountered is not among any characters inside the group.

func (a *NegativeGroup) NFA() *nfa.NFA {

nfa := nfa.New()

startState := nfa.AddState(false)

endState := nfa.AddState(true)

nfa.Start = startState

nfa.AddTransition(startState, endState, func(symbol byte) bool {

avoidList := []byte{}

for _, avoid := range a.ListOfAvoids {

if avoid.Token.Type != tokenizer.Literal {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("NegativeGroup has non-literal token type: %d", avoid.Token.Type))

}

avoidList = append(avoidList, avoid.Token.Character[0])

}

// Transition is valid if the symbol is not present in the avoidList

return !slices.Contains(avoidList, symbol)

})

return nfa

}

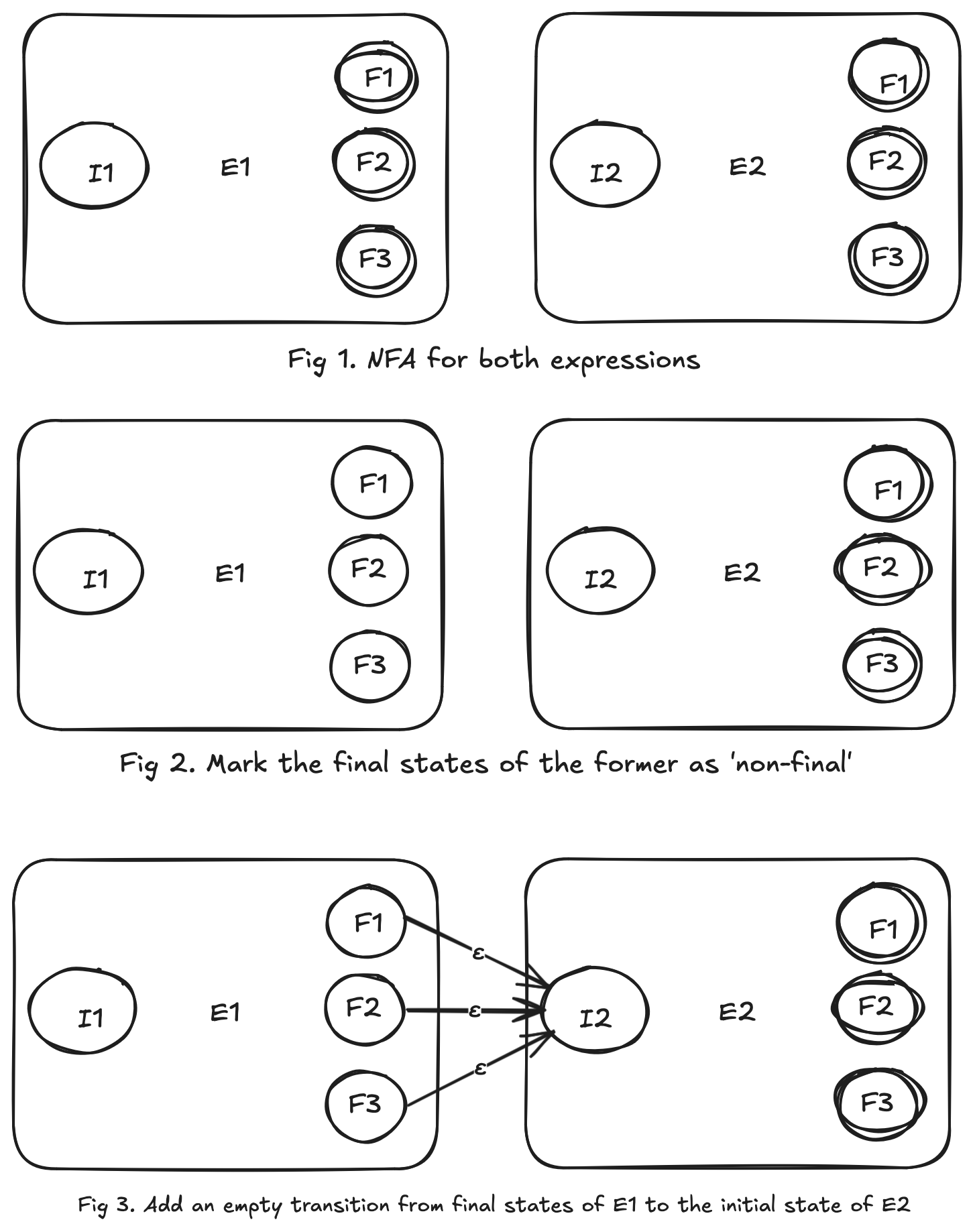

NFA for a sequence of expressions

A regular expression unfortunately doesn’t have a single expression. For example, if we wish to search for the regex cat, we should concatenate (no pun intended) three single character expressions. So, how do we construct a NFA that represents the concatenation of two expressions?

Mark the final states of the first NFA as ’non-final`. Because the NFA should satisfy the string which complies with the former followed by the latter.

Add an empty transition from all the final states of first NFA to the initial state of the second NFA. As simple as that!

func (a *ExpressionsSequence) NFA() *nfa.NFA {

nfas := []*nfa.NFA{}

for _, expr := range *a {

nfas = append(nfas, expr.NFA())

}

return nfa.ConcatList(nfas)

}

func Concat(nfa1, nfa2 *NFA) *NFA {

// record accepting states of nfa1 (before merge)

formerAcceptingStates := []StateID{}

for _, s := range nfa1.States {

if s.IsAccepting {

formerAcceptingStates = append(formerAcceptingStates, s.ID)

}

}

// record accepting states of nfa2 (so we can re-enable them after merge)

latterAcceptingStates := []StateID{}

for _, s := range nfa2.States {

if s.IsAccepting {

latterAcceptingStates = append(latterAcceptingStates, s.ID)

}

}

// Merge states from nfa2 into nfa1

maps.Copy(nfa1.States, nfa2.States)

// Connect accept states of nfa1 (original ones) to start of nfa2 via ε

for _, id := range formerAcceptingStates {

if st, ok := nfa1.States[id]; ok {

st.IsAccepting = false

nfa1.AddTransition(id, nfa2.Start, nil)

}

}

// Re-enable the accepting states from nfa2 (now present inside nfa1.States)

for _, id := range latterAcceptingStates {

if state, ok := nfa1.States[id]; ok {

state.IsAccepting = true

}

}

return nfa1

}

func ConcatList(nfas []*NFA) *NFA {

if len(nfas) == 0 {

return nil

}

if len(nfas) == 1 {

return nfas[0]

}

// Start with the first NFA

result := nfas[0]

// Sequentially concatenate

for i := 1; i < len(nfas); i++ {

result = Concat(result, nfas[i])

}

return result

}

But what’s an empty transition?

An empty transition is such a transition function that allows you to create an extra current state by making a transition ‘for free’. It is marked by the ε (epsilon) character in the transition arrow.

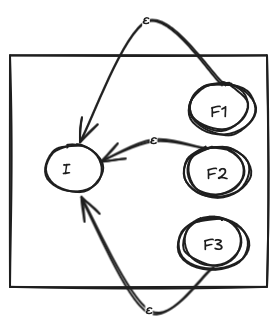

NFA for + quantifier

A ‘one or more’ quantifier, symbolized as the + quantifier approves one or more occurence of the previous expression. For example, ca+ts matches any string which contains c, followed by one or more a, followed by a t, followed by a s.

So, how do we construct an NFA for the + quantifier? We do the following:

- Construct the NFA for the expression in which the quantifier is being applied

- Add an empty transition from all the final states of the NFA to its initial state

But why?

We want to approve any string which satisfies the NFA once or more times. So, by adding an empty transition from all the final states to the initial state, we allow the NFA to approve at least one, or more occurences of that string. After first occurence of the expression, the NFA will have ended up in at least one of the final states. If there are more occurences of that expression, the empty transition will add the initial state to the set of current states. After that, for the subsequent occurences of that expression, the NFA will again end up in one of the final states. Take a moment to absorb that. I cannot phrase that better :(

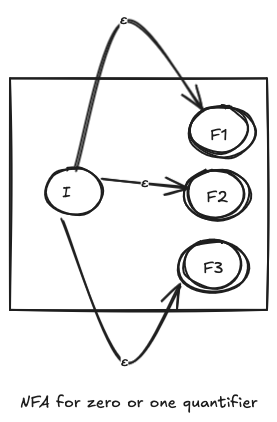

NFA for the ? quantifier

A zero or one quantifier, symbolized as the ? quantifier approves zero or one occurence of the previous expression. For example, ca?ts matches cts or cats.

So, how does the NFA for the ? quantifier look like

- Just add an empty transition from the initial state to all the final states.

This allows the evaluation to ‘skip’ the NFA (complying with the zero occurence).

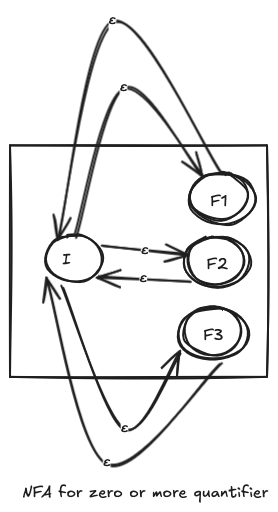

NFA for * quantifier

A zero or more quantifier, symbolized as the * operator approves zero or more occurences of the previous expression. For example, ca*ts matches cts, cats, caaaaats, etc.

So, how does the NFA for the * quantifier look like

- Just add an empty transition from the initial state to all the final states. And, add an empty transition from each final state to the initial state.

This allows the evaluation to skip the NFA (because of the empty transitions from the initial state to the final states), and also approve any number of occurences of the pattern (because of the empty transitions from the final states to the initial state)

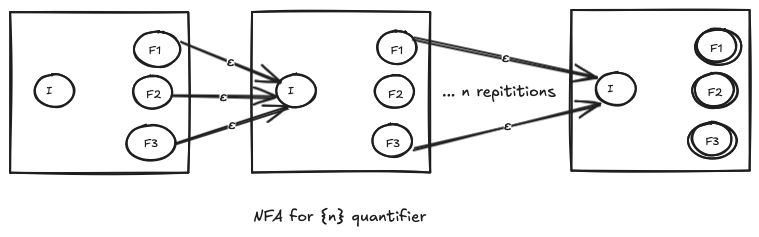

NFA for the {n} quantifier

The {n} quantifier allows for exactly n repititions of the preceeding pattern. For example, \d{4} allows for exactly 4 repititions of a digit character. So, how do we convert the NFA from one that accepts a certain pattern to one that accepts n occurences of that pattern?

- Just concatenate the NFA

ntimes, remove all the intermediate final states as non-final. By concatenate, I mean, add an empty transition from all the the final states of the previous NFA to the initial state of the current NFA.

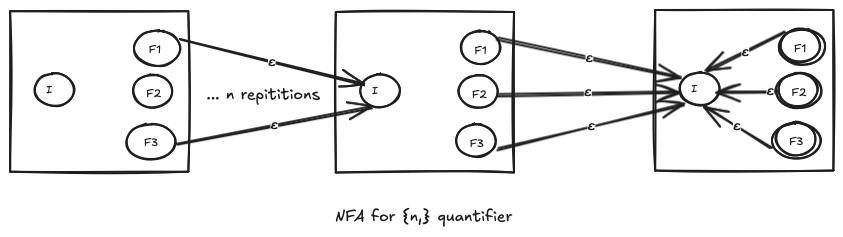

NFA for the {n,} quantifier

The {n,} quantifier allows for exactly n or more than n repititions of the preceeding pattern. For example, ca{3,}ts allows caaats, caaaats, etc.

Just like we created the NFA for the + quantifier, which allowed 1 or more repititions of the certain expression. We start out by creating the NFA for {n,} quantifier by concatenating the NFA n times. But this NFA would approve of expressions which repeat themselves n times. To allow for more than n occurences, we add an empty transition from the final states of the last NFA to the initial state of the last NFA. This way, more than n occurences of the pattern would ’loop around’ the last NFA and be approved.

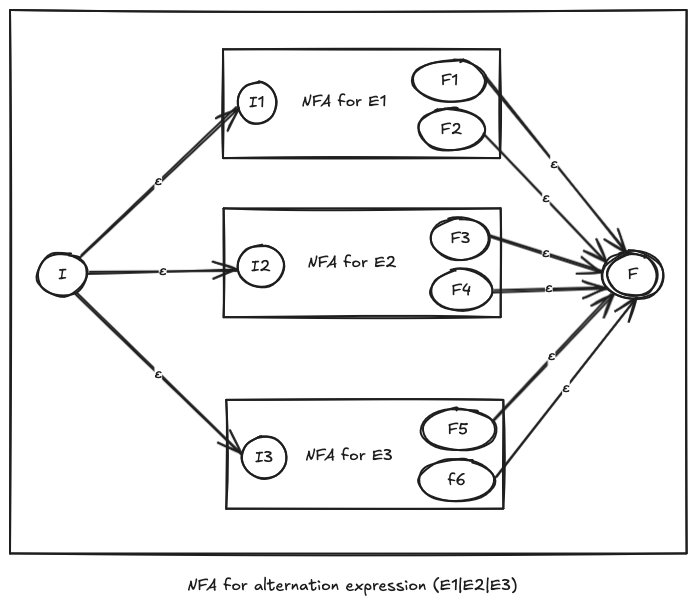

NFA for alternation

Before we tackle the process of building the NFA for the bounded {n,m} quantifier, let’s deal with creating the NFA for the alternation expression. It’s a secret tool that’ll help us later.

The alternation expression matches a string if either of the expressions in alternation options satisfy the string. For example c(aa|bb|xx)ts satisfies caats, cbbts, or cxxts.

So, how do we construct the NFA for the alternation expression?

- Construct the NFA for each expression in the alternation option

- Create a new NFA with an initial state and a final state

- Add an empty transition from the initial state of the new NFA to the initial states of all choices NFA

- Add an empty transition from all the final states of all the choices NFA to the final state of the new NFA

This allows the evaluation loop to take any one of these NFA’s evaluation path due to non-determinancy. In other words, universe splits in to n versions (n is the number of options inside the alternation expression), where each evaluates whether the string matches one of these option.

func (a *Alternation) NFA() *nfa.NFA {

var optionNFAs []*nfa.NFA

for _, exprSeq := range a.Options {

var seqNFAs []*nfa.NFA

for _, expr := range exprSeq {

seqNFAs = append(seqNFAs, expr.NFA())

}

seqNFA := nfa.ConcatList(seqNFAs)

optionNFAs = append(optionNFAs, seqNFA)

}

return nfa.UnionList(optionNFAs)

}

func UnionList(nfas []*NFA) *NFA {

if len(nfas) == 0 {

return nil

}

if len(nfas) == 1 {

return nfas[0]

}

// Create the result NFA

result := New()

// Create new start and accept states

newStart := result.AddState(false)

newAccept := result.AddState(true)

result.Start = newStart

for _, sub := range nfas {

// Merge states from sub NFA into result

maps.Copy(result.States, sub.States)

// ε-transition from new start → sub.Start

result.AddTransition(newStart, sub.Start, nil)

// For each accepting state in the sub NFA

for _, s := range sub.States {

if s.IsAccepting {

s.IsAccepting = false

result.AddTransition(s.ID, newAccept, nil)

}

}

}

return result

}

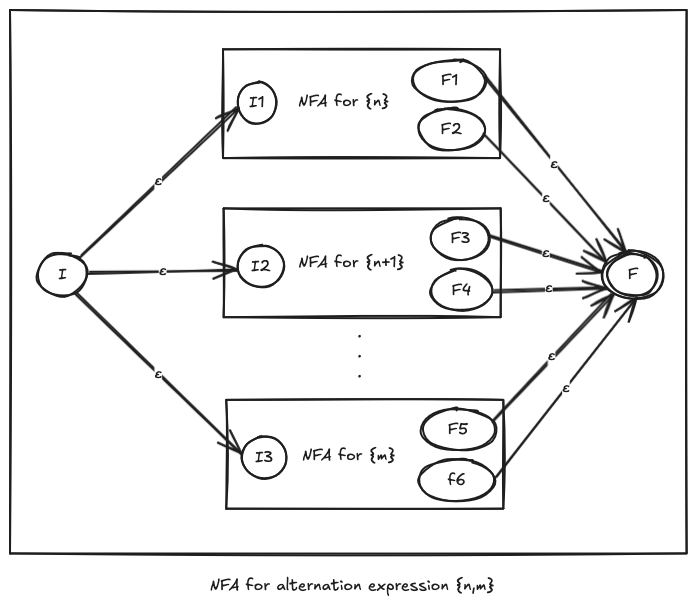

NFA for the {n,m} quantifier

Now that we’ve dealt with creating an NFA for the alternation expression, it’ll be easy to deal with the {n,m} expression, because, this expression allows between n and m occurences of the preceeding pattern. In other words, this expression is an alternation between n, n+1, n+2, ..., m-1, and m occurences of the preceeding pattern. Since we’ve already dealt with exact repitition quantifier {n}, this is a piece of cake!

Now, finally, we can unify the logic of all the quantifier expressions at once.

func (a *Quantifier) NFA() *nfa.NFA {

// Kleene Plus case: Add epsilon transition from all the final states to the initial states

if a.Minimum == 1 && a.Maximum == -1 {

expressionNFA := a.MatchExpression.NFA()

for _, s := range expressionNFA.States {

if s.IsAccepting {

expressionNFA.AddTransition(s.ID, expressionNFA.Start, nil)

}

}

return expressionNFA

}

// Case of 0/1 (?) : Add epsilon trasition from start state to all final states

if a.Minimum == 0 && a.Maximum == 1 {

expressionNFA := a.MatchExpression.NFA()

for _, s := range expressionNFA.States {

if s.IsAccepting {

expressionNFA.AddTransition(expressionNFA.Start, s.ID, nil)

}

}

return expressionNFA

}

// Kleene star case

if a.Minimum == 0 && a.Maximum == -1 {

expressionNFA := a.MatchExpression.NFA()

for _, s := range expressionNFA.States {

// Add empty transitions from start state to all end states

// And add empty transitions from all end states to start state

if s.IsAccepting {

expressionNFA.AddTransition(expressionNFA.Start, s.ID, nil)

expressionNFA.AddTransition(s.ID, expressionNFA.Start, nil)

}

}

return expressionNFA

}

// Minimum == maximum case

if a.Minimum == a.Maximum {

return nfa.RepeatExactly(a.MatchExpression.NFA(), a.Minimum)

}

// For {n,} case

if a.Maximum == -1 {

return nfa.RepeatAtLeast(a.MatchExpression.NFA(), a.Minimum)

}

// For {n,m} case

return nfa.RepeatBetween(a.MatchExpression.NFA(), a.Minimum, a.Maximum)

}

Processing the NFA

Finally, to process the NFA:

- Start with the initial state and compute its epsilon closure

- Make transition to get next set of states

- Compute epsilon closure of the next states

- Loop

If any of the current states end up in the final state, the string matches the regular expression.

func (n *NFA) Process(inputText []byte, withEndAnchor bool) bool {

currentStates := n.EpsilonClosure([]StateID{n.Start})

for _, ch := range inputText {

for currentState := range currentStates {

if !withEndAnchor && n.IsAccepting(currentState) {

return true

}

}

next := make(map[StateID]bool)

// collect reachable states

for stateID := range currentStates {

state := n.States[stateID]

for _, t := range state.Transitions {

if t.SymbolFunc != nil && t.SymbolFunc(ch) {

next[t.To] = true

}

}

}

// Compute epsilon-closure of next states

if len(next) == 0 {

return false // no transition possible — fail early

}

var nextSlice []StateID

for id := range next {

nextSlice = append(nextSlice, id)

}

currentStates = n.EpsilonClosure(nextSlice)

}

// accept if any current state is accepting

// Every text in inputText will have been processed by now, so endAnchor will play no role here

for stateID := range currentStates {

if n.States[stateID].IsAccepting {

return true

}

}

return false

}

Conclusion

That is the whole trick: turn the regex into a machine that knows how to walk through your text, let non-determinism branch into parallel paths, and track every state that survives. Once you understand how each small piece of a pattern becomes a small NFA, the rest is just stitching those pieces together with epsilon transitions.

There is no magic here. Grep works because NFAs are simple, modular and effective. Build the parser, assemble the automaton, run it across the input, and you are done. You now know enough to hack together your own mini grep in a single night, just like Thompson did.

P.S. This article began as a Codecrafters’ Build Your Own Grep challenge solution using Golang. If you are interested in re-building various system programs in your own programming language, check their catalog.